Publications

Ary Stillman Retrospective Exhibition Catalog

Preface

The history of art abounds with examples of artists who have pursued their calling with excellence, indeed, with inspiration quite above the ordinary. Yet, they have not joined by will or circumstance the mainstream of art in their day. While instant glamour may have escaped them—which often proves ephemeral—many stand the test of time better than some of their more heralded peers, as they followed, true only to themselves with an obstinate integrity, their independent and wayward course. Such an artist is Ary Stillman, a figure whose life is more closely linked to the art of the last forty years than is even his oeuvre

The name Ary Stillman is still vividly implanted on the minds of those artists and critics active especially in the New York art scene of the post-war period. Yet how many of these artists and critics can conjure up clearly an image of these forcefully honest landscapes and cityscapes, or the abstractions of the post-war period so clearly born of the era of Jackson Pollock and Bradley Walker Tomlin, yet so far from them in their spiritual content.

It is our aim through this exhibition and illustrated catalogue to give form to this phantom name that is Ary Stillman, and at the same time to honor an artist who chose Houston for his home for the last five years of his life, and which city still harbors almost the entirety of his painted oeuvre.

We are deeply indebted to Richard Teller Hirsch, retired Curator of the James A. Michener Collection of Twentieth Century American Art, for the introduction as well as the body of this catalogue. And of course, to Mrs. Ary Stillman and the artist's entire family, who are the real parents of the exhibition. With a generosity kindled by an understandable enthusiasm for the artist, they placed all of their recollections at the service of Mr. Hirsch, and made available their paintings and drawings for the enjoyment of the Museum's public.

Philippe de Montebello

Director

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

Introduction

Admittedly, there is nothing unusual about a painter whose work undergoes an evolution of style between the early 1920s to the late 1960s.

Aesthetically, Ary Stillman was two distinct American painters within the span of a single lifetime. Admittedly, there is nothing unusual about a painter whose work undergoes an evolution of style between the early 1920s to the late 1960s. In fact, this is possibly the norm in American contemporary or near-contemporary painting. We lack an indelible Rouault, an unswerving Dufy. In the case of Ary Stillman what is extraordinary is that, looking over this array selected from the work of a lifetime, one finds not a gradual evolution but a sudden rift that amounts to the rejection of all of the earlier work, the work done before the break that led to Stillman's adoption of a singular style of which he had given no earlier intimation. That style was to remain without any relapse, any pentimento, his sole vocabulary for the last twenty years of his career. It is this that makes the fascination of the two Ary Stillmans. Both of them were excellent painters, within a given style, but neither the earlier one predicted nor did the later one borrow from the style of the other.

..in the case of Ary Stillman, all evolutionary steps are absent.

Artists who find themselves using several differing idioms in the course of their career most often follow a slow evolution or transformation that leads, ultimately, to partial recall or re-use of portions or even parodies of some previous personal style. Such is the case with Picasso—to take the most obvious example—who reminds us, in his late etchings, of the early period when he was painting lonely figures with an underlying use of line that paid distant homage to Monsieur Ingres. Hans Hofmann evolved as he broke slowly with his earlier dark Munich realism but we also find ourselves indulgent towards any number of other instances where more rapid transformations occurred, whether or not there were recalls of, or allusions to, earlier work in an artist's later efforts. But, in the case of the two Stillmans, all evolutionary steps are absent. In his later work we find not even a cryptic recall of anything done earlier, lust as nothing in the earlier work provides mystical signs or esoteric symbols which, with hindsight, we can interpret as having led to the final statements. More importantly, there were no intermediate, piecemeal abjurations, a number of halfway stopovers, such as Rothko's Surrealist entanglements, Kline's bar paintings in Greenwich Village between his railroad trains' primitivism and his phone directory calligrams that prefigured those great black slashes on monumental rectangles of white canvas. Thomas Hess, who knew Ary Stillman and respected his art, has recalled for this writer "the conversion" Elaine De Kooning has attributed to many post-World War II artists as a phenomenon many of them underwent collectively. She forgot that, for some, satori was a step in an ongoing development, a landing on the staircase to fame or final style. Ary Stillman knew no such intermediate progressions.

The background of the first Ary Stillman offers few special surprises, although it required enormous personal stamina and quietly heroic dedication for him to emerge as an accepted artist. All his tenacious ambitions, his singleness of purpose, explain the flavor of the paintings of those struggling, intense years. Of course such things had not infrequently happened to others, molding other temperaments. Thus, as we respect this man so are we witness to the quiet fervor latent in what he could do: the early work has this measured excellence, a commanding integrity.

The birth of the second Ary Stillman resulted directly from the pangs of tragedy, intensifying, as World War II became a permanent part of the American consciousness. Like many another artist confronted by the brutalities of an unprecedented Weltgeist, Stillman took stock of what he had been doing up to then. He looked at his oeuvre, asking the stark questions suddenly propounded by the world drama, which had and still surrounded him. Many sensitive souls in the arts were similarly affected—as had also been the case when World War I destroyed the serene axioms of a previous American scene. The new Stillman, thus, found himself rejecting all that he had accomplished, rejecting, as well, the position which his work had slowly given him; and more importantly, adopting, compulsively, the bases of his unquestioning need to find a sense of new purpose. His Paris of the Salons lay in ashes; the aesthetics of his boy, and manhood quenched his inner fire no longer, hut lay bitter on the tongue. Encircled with skeletons, tomorrow beckoned, intransigent, unbeholden and demanding.

As any creative artist, deafened by the paeans of destruction, what Ary Stillman's purposes had been could and would no longer suffice to sustain further effort. Rejection, over agonizing days and hours of meditation—even a verdant Central Park no therapeutic distraction—was an inescapable dilemma; the shadow-light within his soul's insufficient bomb shelter had made the sweet light, to which he had earlier responded, into a piercing memory of lost illusion. His resulting private vacuum, familiar to all mystics and to a respectable army of saints, devoured him. The time found his spirit as that of so many others, both numbingly sterile and painfully pregnant.

Even when possessed by despair no truly creative temperament, however, can dissociate life from creativity. Hence, do we witness the Ary Stillman II of the late 40s, finally looking forward, all accumulated baggage left behind, and entering into an entirely new plastic and graphic field.

It is, therefore, not a semantic trick to date from 1945 Stillman-as-amnesiac, an artist who had unlearned all previous memories, all previous skills and aims. What he gave us was a new artist to consider, producing works which, though tragically motivated, were oriented entirely towards some strange and, as yet, unconceived future. The paradox that despair, though absolute, should lead to novel creation (and not to re-creation) is but one of the ironies of the artistic daemon that besets its elect.

We are familiar with the growing interest in abstraction aroused by world tragedy among many of our artists once the transplanted American Surrealist "revival" in which Rothko, Donati and so many others had participated, abated and died. These mutating artists, however, almost always carried with them, as was mentioned, the memories or the nostalgia of earlier times and earlier work. Not so, Ary Stillman II. For him, the world was not the familiar one with new elements added, others distorted or ablated. Rather, it was a new world entirely that sprang from no ancient, perennial, recollected roots, nothing but what made old memories intolerable and earlier goals ridiculous, vacant—as a battlefield is vacant when the guns are stilled.

In actual fact, as this exhibition demonstrates, there was, of course, but one unalterable Ary Stillman, fated in his painterly persistence: the man who had been the poor Jewish boy of Hretzk, possessed with the desire to draw, who had taught slower but less indigent students for kopeks in nearby Byelorussian Slutzk, to the sole end that the Imperial School of Art at Vilna—accepting him in spite of the overwhelming odds against it—might teach him painting, the year being the revolutionary one of 1905. Then we witness this hungry student without means aspiring to the greatest of all impossible goals, the Imperial Academy of St. Petersburg. Plans changed, and from 1908, a mere three years later, we have a portrait painted by Ary Stillman that appears strangely out of place in the exhibition (Cat. No.1). It is a harsh realistic portrait, smoothly brushed, with hard linear outlines, without mystery in its darkness, unaware of the magic of light. It is unencumbered, by flattery or sentimentality, although the subject, Mrs. Brodkey, was the artist's great aunt, the wife of the owner of a jewelry store in Sioux City, Iowa who had brought him to this country in 1907. This stiff painting is included in this retrospective because, in its stark way, the very fact of its existence, the fact that Ary Stillman, aged 17, could conceivably, given his origins, have painted it, good, bad or indifferent, represents a triumph over apparently insurmountable odds. It demonstrates that this lad of seventeen, though born into the grinding darkness of Russia's most primitive rural deprivation and ignorance, had extracted, by the standards of the times, a remarkable painterly competence from the narrow technical teachings of the Imperial Art School in Vilna. His origins should have barred him without recourse from such training seemingly unattainable. We may find that this portrait displays an inculcated meagerness of means, we may be justifiably critical of what this picture tells of the XIXth century studio recipes handed out by the Imperial Art School. But that Stillman, only fifteen years after his birth into the utter hopelessness of his native countryside, should have fought for and won any exposure at all to such practices should color all our later assessments of both man and artist.

Devoid of self-pity, doggedly oblivious to what should have been his pre-ordained station in life, equipped with fantastic persistence, humble but gifted with unassailable pride, Ary Stillman had been born to be an artist and, precociously, he knew it.

Then, years later, after fulfilling his early promise to bring his mother and the rest of the family to the U.S.; after those years of working for his uncle in the jewelry store in Sioux City, Iowa; painting in the loneliness of the shop's back room took him to only the shortest of stints at Chicago's Art Institute. After that came the poverty of those Lower East Side years in New York, with eager night classes at the Jewish Educational Alliance, study at the National Academy of Design and yet other evenings at the Art Students' League, all these revelations leading to the seven-year adventure of Paris, of Europe, of the Mediterranean world, North Africa, Palestine. After returning for a single year in America, other years back in Paris again further developed, refined and matured a sensibility that had opened the Salons to him in France and major galleries in New York and which would, one day, sustain the second Ary Stillman in the untrodden jungle paths of his later expression. The Sienese had fascinated him, the Assisi Giottos enthralled; his cult of Cézanne had enticed him for a short time, but not to goals foreign to his innate ones; as with Van Gogh's Provence, he saw only with his own eyes, not through those of the Seer of Aries or those of the Man of Aix. André Lhote ("Heureusement que dans géometrie il y a géo!") had been a fleeting mentor. Othon Friesz invited Stillman to exhibit with him at the Salon d'Automne. Neither the teacher nor the elder marked Ary's personal manner. Other friendships among the eminent in the arts seemed to develop naturally around Stillman. His monthly open house in Paris was well attended, not only by aspiring French artists and the American painters of passage but by the leaders of the Salons, the Gallery-entrenched and a number of critics. Leo Stein was among the latter, Ary finding him a better talker than writer; both agreeing that Gertrude was a ''fraud.'' His first one-man show was at Bernheim Jeune's, successful, well reviewed. It was 1928. Stillman was 37. It appeared to his American friends in Paris, as it would to those in New York when he returned to America the following year, that he was a peintre arrive, in the French manner.

He had his first American one-man show at the Fifth Avenue Ainslie Galleries, followed immediately by others in such places as the City Art Museum of St Louis, the Art Institute of Omaha, as well as in Tulsa and his old stomping ground of Sioux City. This was in its way overnight success. Nothing less than the stockmarket crash could have arrested such a beginning. The critics of 1929 were hardly even tuning up for their proclamations of ''Regionalism'' as the approved style of the day to come. ''Socially conscious'' painting was still several years in the offing. Remarks about the ''Frenchness'' of Stillman's works were hardly negative whispers that year. Only the tenets born of the Depression would change their tenor.

For one thing, his painting was not servily imbued with the Gallicism of any particular leading Frenchman or school of Parisians. Stillman was very much his own man when he looked at the night crowds catching the lights of a New York canyon; very much his own man—not a pale Bonnard, nor a hard-edge Vuillard, nor a passionless Mediterranean—when painting a still-life before an open window looking towards the damp greens of a wood land, Barbizon forgotten, Lhote rejected. His Frenchness was not in any way equivalent to that of such a fascinated Parisian-for-a-time as Robert Henri, just as his New York accent was not that of his friend John Sloan. Years earlier he would not have been a ''ninth'' to join the Eight exhibiting at the Macbeth Gallery.

Had his friend Othon Friesz, a sponsor of his work, been able to convert him into seeing the Mediterranean as a heavy geometry of raw or harsh outlines? He knew all the painters in Paris--by their works at least--but his painting had remained steadfastly his own. Stylistically he might waver, under the impact (he favored that energetic word) of a given scene, a given subject. His painting was prompted by mood or emotion; it did not waver, however, from the encounter with some other artist, someone else's work. He could be, and was, selectively gregarious; he was not a joiner, much less a disciple, even less a conforming calculating plagiarist. Independence was a life trait, quiet, unassuming, unswerving.

When choosing to paint a girl's head during van Dongen's most fashionable years, Stillman found in his brush and treatment a delicacy that the more famous of the two missed while, patently, seeking it time after time. His painting of a somewhat dismal village setting under the snow (Cat. No.7) would mislead one to think that Stillman had never laid eyes on a Vlaminck although, in those years, any short stroll in Paris would have exposed him to the Flemish painter's rutted winter streets, vacant under racing skies. On the contrary, Stillman's village street, dusted with snow, the small church warmed by the minute color variations of the granite of the Massif Central, is a study of atmosphere, of hushed quietude, of architecture and, hence, though unseen behind those walls, of people, rooted, unperturbed and as stolid as the immemorial hillside lovingly quarried.

Elsewhere in the same area, an unrelieved gray overcast manages to convey a sense of filtered sunlight, bathing peasant dwellings and barns, their quiescent presence seeming serenely apposite rather than obtrusively possessive or quaintly rustic. Cézanne, whom Stillman revered and understood-but never plagiarized-would have found the motif claustrophobic; other French painters probably would not even have noticed the scene, too sheltered for traditional atmospheric perspective; Lhote would have ''Geometricized'' it; Soutine, through the cosmic chaos of his transmogrifying ego, would have discerned only the volcanic upheaval that had compressed it fiercely into what Stillman simply saw as its gentle nestling. More than merely seeing, he felt. The still grays of the overcast were to him but a sieve for the rays of a boundless, silent sunlight falling equally on everything's serenity, its rightness of mood, place and time. The result, a pious paean to the land, tempests of molten mountains long stilled by the easy flow of ages, a place for man to root himself deeply; all vast horizons foreign, beyond those hills whose closeness he savored.

The Post Office Square of a Mediterranean Cassis (seen in the Bernheim Jeune exhibition and, later, in this country) offered other and more enticing pitfalls. Stillman gives us here, not a dazzling burst of sunshine, nor, it must be emphasized, reminiscences of Van Gogh's modeling by brush stroke and impasto, nor some Cézannesque spectrum flickering in short oblique parallel strokes, nor yet allusions to Cézanne's fervor of contrapuntal planes bathed in a dancing refracted light. What Stillman gives us is Stillman's own Provence: a deserted square, the setting for a commanding, if leafless tree, a subdued sky whose light is spread evenly, refusing facile contrasts, a place, La Place de la Poste (Cat. No.6), not a stage set. Le Sidaner, perhaps, would have liked this painting; Friesz would have added his contours, neglecting the imponderables in favor of the earthy ponderous; Derain, needing more room, would have strode farther up the hillside for a broader view. The Place is deserted but not abandoned, as if this were the withdrawn hour for the rhythmic breathing of the siesta's interim. It is Stillman's hour, here.

Crowds in Stillman's painting of those years were those he had watched and analyzed endlessly—then to paint them, distilled, into tight constellations of color and rippling shadow —in New York; among the Indians above Taos; in Mexico; on Coney Island (Cat. No.10); or at the World's Fair (Cat. No.12). He pondered crowds, their movement, their eddies and purposeless tides; he watched them in the light filtering down from the upper reaches of skyscraper canyons, jostling, an undifferentiated multitude in the lights of Time Square's nocturnal dazzle and flicker (Cat. No.9) or the morning gray between gray stone masses whose pinnacles alone, roseate, respond to a lust-risen misty sun. The dancers in the Salon Mexico (Cat. No.11), under the harsh lights, the reflections from the brass band, endowed with the swirling subdued color of ample garments, form a picture to which Copeland also responded with his piece of the same name. These are far removed from even hinting at the purposes implicit in Manet's painting of a guinguette or Robert Henri's Bal Tabarin. That all this collective movement of individuals (seen as a single entity) was Stillman's gift as an observer, a painterly man receptive of moods but not of methods, is demonstrated by earlier scenes which included single figures and, also, by his portraits.

Some of these, omitted from this exhibition, could be motifs for an arrangement of color or a pretext for dynamic distortion: the first Ary Stillman sought no such effects, needed none, imposed none on the reality of the moment. His nerve endings made him, though in no way passive, a receiver. Where there was peace, his intuition heightened the image of such quietude. Where there had been explosions of rhythmic color, Taos Indian dances vibrated on the walls of the Galerie Zak in his second Paris one-man show. The harsh, repetitive beat was a frenzy of man's garishness encompassed by the cosmic silence of whispering deserts of time. Alas, all of these latter works, left in France, seem not to have survived the great war.

The second Ary Stillman was a strange phenomenon maturing towards a new flowering through tortured periods of contemplation and then of hollow inactivity; through detached participation in the discussions at ''The Club'' (so well chronicled by Irving Sandler); of shared reveries and speculations in Central Park, and that special emotional blankness known to so many creative temperaments of those years. The painterly realities of a mere few years earlier, though genuine, had been vastly devastated by the overpowering aftermath of a World War and seemed now to be comparatively negligible casualties. There was no longer a utopian city of the mind that could be resurrected and rebuilt with materials salvaged from the dust of this traumatic rubble. Life—it seemed to many an artistic mind, some as sensitive as Ary's, others as tough as George Grosz's in his The Upheaval of Nothingness—might be more vacuum than enrichment; more riddle than answer. Warsaw Old Town might have Bellotto's facades rebuilt, but Warsaw's Old Town would be, forever, only a New Sham—Bellotto's reality, in spite of all externals, gone, lost, a figment. But one lived still, paint could still smell good when it did not mock with the reek of a mental emetic. One lives, the lust for life a mocking despair, while yet a flame lingers fitfully, remnant of a cosmic death pyre or the paradox of a creative urge, who knows? And should one care? ''The Irascribles'' looking forward, which Dada had not, after that earlier holocaust of World War I, became what, eventually; we would call the School of New York. Ary Stillman found himself—though accepted and shown at Wildenstein's and elsewhere—not quite one of them, though he had helped to form the Federation of Modern Painters and Sculptors. The Macbeth Gallery (shades of the ''Eight's'' iconoclasm displayed there 38 years earlier) gave his new work a one-man show. And others were to follow.

To the man who was later to sign his painting merely ''Ary'', this was not new. He had been accepted in New York before, shown and carped at a bit for the ''Frenchness'' of his work, while, as was said, he had been immune to the styles or mannerisms of the French. Now, in his new incarnation, he was to be confronted by the same dilemma caused by confusing his work with that of others, praised with them, or cursed for this assumed identity of aims, all at the critics' whim.

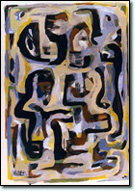

An action painter, an abstract expressionist he was not. His works at this time were not gestural, random in the fashionable way. Nor did they belong to the splash school—what the French, the new French, called tachisme. Somewhere between the structural and a fluid world of gem-like opalescence Ary Stillman painted his particular vision. Bowing only once to the new notions, at least in terms of size, he attempted, beyond his physical strength, stunningly, the large format. But Ary II had had small beginnings after the war, dabbling —only dabbling he thought— with smallish drawings, the paper smudged. The suggested planes were honed, however, with penciled areas (Cat. No. 16); contours lit by insubstantial lines of scratched-out hatchings, edges of form, rhythmic sonnets of form (Cat. No. 17), all references to the past or the remembered semblance of terrestrial things absent, as if Ary's eye had lost its memory—leaving acuteness only, and only for what grew beneath his hand. Three woodcuts mark this time (Cat. No. 23) —in an ''edition'' of four quite differing impressions—and two lithographs, printed for self and friends. Biomorphic or crystalline, the drawings, all of them smallish (Cat. No.25), create a world of ordered depth receding into enigmatic shadow, as the quiet recedes into an opacity that is not barrier but a beckoning to other patterns, just beyond yet further depths of sight. Many of these patternings ''happened'' at Cape Cod. And there were other travels, old sights seen with a new vision: Majorca, Paris (In The Studio, Cat. No.24), for an unfruitful time, and Siena, where Ary became convinced, once again, that truth had once been captured long ago, and Catalonia, where glimpses of the sacramental stimulated both the inner and the outer eye, where starkness was not a naiveté but a symbolic sufficiency. Then to Mexico again, temples resplendent in their decay, asking the questions they were once built to answer (Cat. No.26), hieroglyphs upon the jungle, as hieratic as the rituals, familiar to Stillman, of the Greek Orthodoxy but more hermetic. Ary II was now equipped for the important works of those later years, their opulent creativity, their vigor, their mystery. He chose some titles for these works that are clearly directed at those too unperceptive to divine what had brought them into being, the secret intent that made them throb from within. Other titles, such as Coptic (Cat. No.31) or In the Beginning (Cat. Nos. 36 and 37) convey Ary's awareness of the poignancy of renewal or of youth imbedded in ruin or, more disturbingly, the riddles of vibrant life mystically immobilized in death. Such allusions explicate, as well, much of the fervor evident in layered veilings of neutral pigment beneath which lie the clear colors of the underpainting, subdued, in turn, or strengthened by apertures revealing pure blacks, pure color or emphasized by black lines superimposed on ghostly intimations. The veilings are not the muting of some instrument, but the pauses that orchestrate a complexity of themes into controlled moments of revelation (Archaic Images, Cat. No.30). This is true particularly of the gouaches of those years. Oils and acrylics Stillman used differently, smoothness in one canvas being followed by almost granular impasti in another, free compositions of one year float upon backgrounds of seemingly burnished golden browns, as jewel facets magnifying icons by cryptic allusions long forgotten.

As in Blue Accent (Cat. No.19), black lines often encompass areas of color set upon a neutral background. Elsewhere color, muted or opalescent, cooled greens, seemingly translucent, seemingly back-lighted, are the indeterminate ground for vigorous flights of black lines rising, curving into partial, upward-thrusting, structural, tensioned ogees. Stillman came back to these concepts as if stimulated by their poetic energy, their purposeful kinetic power. These were explorations that could have satisfied many an artist to remain within the enchantment of their spontaneous perpetual motion. Such works, to a more static man, might—legitimately—have become his successful personal style, the griffe which the first Ary Stillman never quite achieved. But no.

Our second Ary, the explorer, continued on his chosen course and by each discovery was led still onwards and beyond. Often he parallels this or that notion which may evoke another painter's name: Gromaire, a name one historian has mentioned, for some of the black-stroke-over-color works, as in Rhythms in Space (Cat. No.29); but on examination such an appraisal fails to bridge a fundamental divergence; Gromaire's aims and Ary's in no way coincided. There are box-like figurations in Stillman's canvases at one point, as in Improvisation (Cat. No.43); but not those of the early Gottlieb. There are wide-stroke grisailles made with a flat brush, true, but Tomlin's preciosity with which Stillman was familiar, is absent here in Black and White, No.3 (Cat. No. 27), just as is Tomlin's self-conscious embroidering of the painted surface. Such vocabularies Ary used solely to his very personally unique ends and the results have a mystery of realities veiled over by yet others that leave Tomlin superficial, charming, a stranger in a quite different world. Every critical study of Tomlin has stressed the effete preciosity so remote from Stillman's fervor. And charm—in all but the esoteric meaning of the term—is never found in our explorer's work.

When a man does not borrow from his former self for either allusion, form, idiom or theme, it should be obvious, one would hope, though this opinion, as any other, may be disputed, that it is in vain that the critic look for borrowings from other artists in the artist's most original work. Ary had responded to the Sienese, the early Catalonians and, living in Mexico or within his studio in Houston, he pondered Mayan riddles. He worked to say powerful things evoked from strange dimensions of time, unmindful of modish galleries. The Mayas (and the Incas) haunted him; his brush moved boldly in answer to echoes within his mind as his intuition evoked them. But no false, if fragrant exoticism is here, such as Bali had imposed upon a clever Covarrubias. The Birth of the Snake God (Cat. No.32) is no pastiche of glyph, no ersatz for a labored stone rubbing, no copy of a carving, even less the work of some hypnotic Morris Graves, recreating nature or giving the spirit a personal incarnation. What it is is a free communion in strong, effervescing terms with something felt, the feeling transmuting the sensed ambiance of another, timeless cosmos; a coincidence of emotions on a high plane of visions somehow encountered in a universal mystery, shared, with Them, by him, for us. More specific evocations arise, unlabored but yet distilled, in such powerful works as Two Caciques (Cat. No.26). The procession, the processional, hieratic undoubtedly, but not archaeological, also abounds in these recollections of the unknown, the unseen: Ceremonial and Saga (Cat. Nos. 38 and 40).

Such, from the depths of despair, from the cavernous vacuum left by war-shattered realities, were the flowerings, which the second Ary Stillman brought forth. He had once been a painter who saw with feeling. In the last years, the years of rebirth, feeling had made him surpass response to mere outer visual perception. Growing in strength, as in Untitled (Cat. No.47), though his body grew weaker, commanding obedience from his tools to state fervently, decisively, the inner dictates of his intuitive echoings, Ary Stillman, the visionary, triumphed, his work achieved, destiny fulfilled—Empyrean glimpsed beyond the veil.

Richard Teller Hirsch

Copyright © 2002-2007 The Stillman-Lack Foundation.

All text and images on this site may not be published, broadcast, or distributed in any form without the prior written permission of The Stillman-Lack Foundation.