Press, The 2 Realities of Ary Stillman

February 27, 1972

Houston Post

by Eleanor Freed

Occasionally today there are artists who are constant successes, catapulted to fame and fortune by the entente cordials which frequently exists between museum curator, metropolitan art dealer and serious art journals, but for the most part the creative agony remains an ongoing trauma in a very private domain.

Sadly, the ultimate external fruition, recognition such as accorded by a museum retrospective, comes – if it comes at all – too often as a post-modern reassessment. Such is the case with an exhibition of the work of Ary Stillman (1891-1967) which has just opened at the Museum of Fine Arts.

One is immediately confronted with the evidence of a psychic dichotomy, an earlier dedication to transcribing the surface reality abruptly terminated by a later compulsion to probe the Inner self and to paint the inner reality.

Typical of many mature artists with established styles at the time that abstraction became the Esperanto of the day, a former plastic vocabulary had to be discarded while a new one was first to be discovered and then mastered. After the holocaust of World War II, Stillman realized that he could not go on painting the crowd scenes, the ambience of the city, the vistas of Paris or portraits. Seeking his own way, he began to play with charcoal on paper. "I felt that maybe through an accident or subconscious movement, I will get something from within myself."Hundreds of these charcoal drawings "opened up a direction where to jump over the fence. I saw possibilities for compositions, for things that contain certain realities." Later, in some reminiscences which his devoted widow, Frances, made available to me, Stillman said of abstraction: "Not only does the artist create a plastic unit but he offers an opportunity to others with imagination creatively to look at it the same as music…"

Speaking of his radical departure from figurative painting, he said, "Even years before my going to Mexico I had completely broken away from painting surface realities. But it was in Mexico that the inner reality began more and more to emerge, that I felt more and more its essence. It was for me a period when fantasy became paintable, or when I invaded the world of fantasy. I was completely involved in the mysticism of the subconscious…”

The exhibition is accompanied by a handsome catalogue with a perceptive text by Richard Teller Hirsh, former director of the Michener Collection, who has just been made director of the New Zealand Museum. Philippe de Montebello, director of Houston’s Museum of Fine Arts (now the director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City), has edited the extensive oeuvre which remains a part of the Stillman-Lack Foundation in Houston (Stillman spent the final five years of his life here). The major stress has been placed by de Montebello on the years after Stillman’s breakthrough into abstraction.

Although Stillman was a friend of many of the painters of the New York School and a member of the “Eighth Street Club” (De Kooning, Ad Reinhardt, Franz Kline, John Cage, Morton Feldman, Jack Tworkov, Larry Rivers, Frank O’Hara, etc.), he was always a loner, on the fringes of whatever organization he tentatively joined. Stillman wasn’t group-oriented, remaining always a detached observer of the scene. Yet during the decade 1945-1954, he indeed made the scene through numerous exhibitions in top drawer galleries and significant museum group exhibits.

One-man shows at Midtown Gallery followed Bernheim Jeune and earlier Paris exhibitions…then Andre-Seligmann, Macbeth where he presented the first abstract show (1946) in their then 50-year history and five successive exhibits at Bertha Schaefer. Although critical reviews were of a high caliber, his collectors remained limited and he never achieved any degree of financial security or special singling out for museum one-man shows.

Salon Mexico

1940, oil on canvas, 23 1/2 x 29 in.,

[Ary Stillman Green Room,

University of Houston,

Moores School of Music, TX]

The early representational paintings such as "Sideshow, Coney Island" of 1937 "Salon Mexico (El Baile)" and "Worlds Fair," both from 1940, are full of movement and imbued with the zest and swirl of life. Despite the fact that his color is more subdued and his faces and figures less distinct, Stillman projects vitality as strongly, though perhaps not as earthy, as did Orozco in his early dance hall paintings or Reginald Marsh in his urban commentaries.

Although at one time on the roll of W.P.A. artists, Stillman was never a social protest painter and relatively briefly a social realist. He had been too deeply affected by his years based in Paris (1922-1933) and the vast scope and residual influence from his extensive travels. Later, when he began to paint in an abstract manner, as if on call to an inner genie, he summoned up memories of the Romanesque, Byzantine, Sienese, Catalonian, African, Mayan and Incan from which he developed rhythms and patterns based on a pastiche of many civilizations.

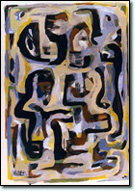

Strolling around the two rooms of the exhibition, one of the initial impacts is how Stillman employed black and white as colors in his often writhing, sometimes syncopated surfaces. In most of these works there is a sort of Danse Macabre between the romantic, intuitive Stillman and the analytical, ritualistic Stillman.

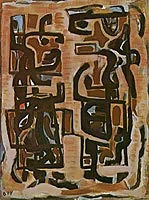

Dos Caciques

1960, acrylic on canvas,

24 x 18 in.,

[Denver Art Museum, CO]

Sometimes I am reminded of Paul Klee by the ominous black lines that appeared through so much of Stillman and during the end of Klee’s life, as well as their mutual dependence on music. Both painters ignored conventional perspective. Stillman’s flat field, often subdivided into surface grids, could be glyphs from previous civilizations. In Stillman, irregular lines of color often encompass and contain the painting as an exterior frame. There is much underpainting and layering and broken staccato patterns. Shadows and contours hold frequent turbulent dialogues.

I am also reminded of the dance patterns of Carlos Merida and his extraction of Indian myth; however, there is a finite order and clean-cut geometry in Merida, where in Stillman there is a looseness, a break-up of forms, a restless probing into the transitory nature of space. In this Stillman shares rapport with Gorky and an earlier Pollock.

Frances Stillman’s diary of her late husband is most interesting…how a poor boy from Byelorussia migrated to Sioux City, Iowa…thence to New York, Paris with trips all over three continents before his many years in Cuernavaca and lastly in Houston. Life…the essentials of existence…and a muse, years of bad health…inner torments and struggle…the world seemingly passing him by during the last decade.

What we see poured out before us in a most sympathetic setting is the serious, often difficult, and sometimes beautiful work of a sensitive, tortured creative spirit. Ary Stillman was a man whose entire life was devoted to a search for truth, the outer and then the inner reality as he plumbed decades of recollections of things seen; expressed but above all felt.